When developers propose new apartments, some opponents get downright creative in their efforts to stop them.

Recently in San Francisco, opponents of an 100% affordable housing project argued that shadows from the building would deprive schoolchildren of vitamin D, and warned the units would be “‘magnets’ for addicts,” according to the San Francisco Chronicle. Several Texas cities are attempting to undermine new state-level zoning reforms by requiring multifamily projects to include ritzy amenities such as dog parks, sports courts, rooftop lounges and fitness centers with a sauna or steam room, Reason reported.

Across the country, there are new tactics to slow or stop apartment construction.

Nicole Upano, assistant vice president of housing policy and regulatory affairs at the National Apartment Association, noted such pushback illustrates how “not in my backyard” sentiment has evolved, creating roadblocks that can be as effective as outright bans. Common complaints are that more parking is needed, the project doesn’t fit the character of the community and environmental requirements should be more strict.

“While the language varies, the result is often the same: fewer homes built in places that need them most,” Upano told Multifamily Dive. “We believe we should be using all of the tools in our toolbox to address the undersupply of the housing crisis in the U.S.”

In Boston, Upano noted strict minimum lot sizes, height caps and building codes already make development difficult, and an inclusionary zoning policy piles on by requiring projects of seven units or more to include 20% income-restricted housing before any relief from those restrictions is even considered.

By contrast, Florida’s Live Local Act has streamlined approvals, offers tax exemptions for affordable housing built on religious institution property and incentivizes employer-sponsored housing.

Creative obstacles to housing

David Block, director of development with Evergreen Real Estate Group, frequently deals with NIMBY issues in community meetings and throughout the development process. He said the pushback his team encounters often depends on where the project is located.

“Most of the projects we’ve done in core cities like Chicago or Denver don’t run into much NIMBY resistance, because people there see the need for affordable housing,” Block said. “But in suburban locations, it’s more challenging—you run into zoning battles and the NIMBY arguments.”

He recalled one particularly bitter fight over a plan to adaptively reuse an old factory building in a western Chicago suburb.

“Very quickly we got into the ugliest ‘we don’t want those people in our neighborhood’ kind of conversations,” Block said. “There were yard signs, a nasty Facebook campaign, packed public meetings. We went through months of hearings and had the council votes we needed, until one neighbor filed a petition that triggered a supermajority requirement. We came up one vote short, and the project died. That building is still sitting empty.”

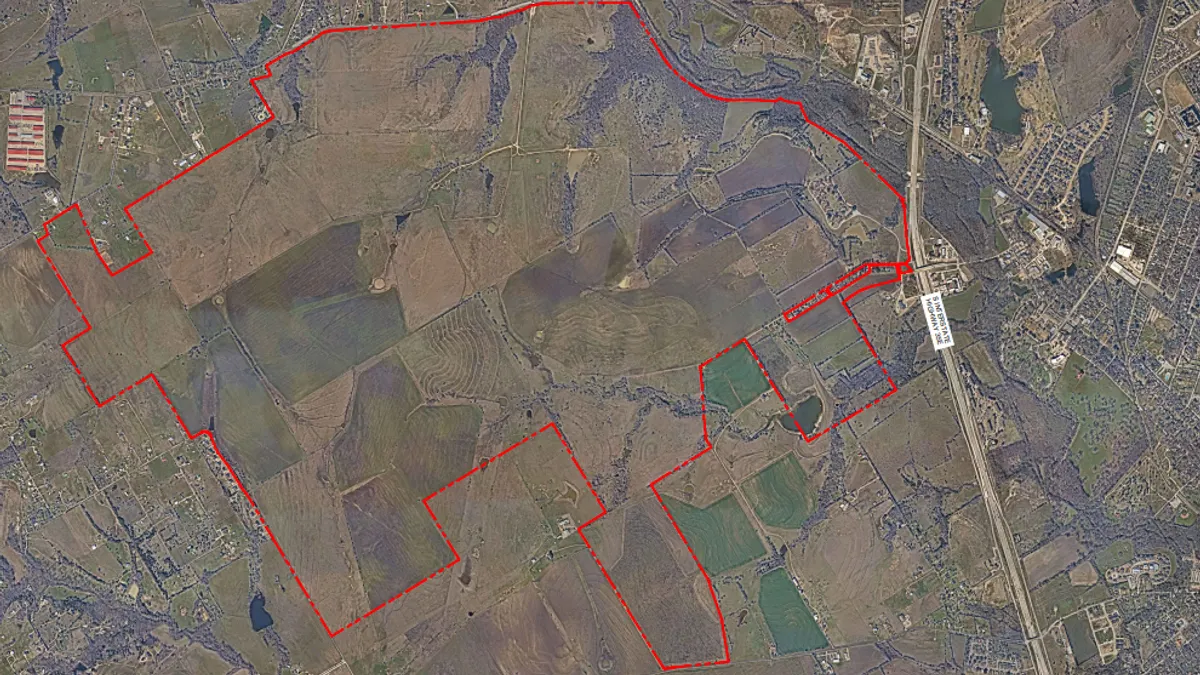

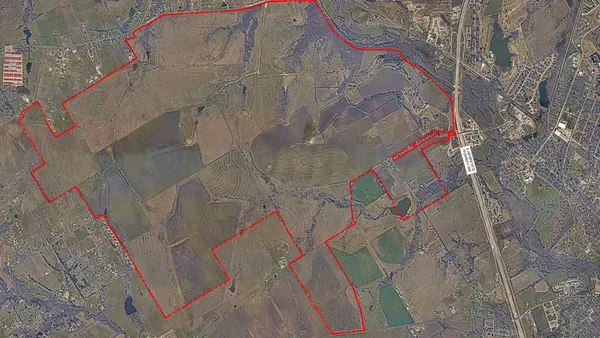

Joshua Zinder, managing partner of architecture and development firm JZA+D in Princeton, New Jersey, shared a story about a housing fight in West Windsor, New Jersey, where the Howard Hughes Corp. purchased a 658-acre site formerly zoned for industrial use with the goal of rezoning and redeveloping it with housing and amenities, basically creating a new town center.

“The NIMBYs said, ‘We don’t need a second downtown’ but I’ve been there, and they don’t have a downtown to speak of,” Zinder said. “They also expressed that there would be increased traffic. Maybe most absurd, they complained about the likely increase in kids attending the school system, without realizing that the increased property tax revenue would improve the school system for everyone.”

Christopher J. Calton, a research fellow in housing and homelessness at the Oakland-based Independent Institute, said many of the objections raised in housing fights are less about the stated reasons and more about preserving neighborhood exclusivity.

He also pointed to research showing that lawsuits filed under California’s Environmental Quality Act are overwhelmingly used to block projects in urban cores rather than to protect open space. In late June, California Gov. Gavin Newsom signed legislation as part of the 2025-2026 state budget that reformed CEQA to make it easier to deliver housing and infrastructure projects.

“The vast majority of environmental lawsuits in California aren’t about protecting the environment at all—they’re about blocking infill housing, which is actually the most environmentally friendly kind of development,” he said.

Sometimes, Calton added, the objections reach the level of parody.

“Absurd justifications like Woodside declaring itself a mountain lion sanctuary show how far some localities will go to stop new housing,” he said. “Discretionary permitting gives opponents endless opportunities to appeal and delay projects, which is why permit reform is one of the most important fixes we need.”