Attorney Brad Butler is a partner in the Louisville, Kentucky, office of Frost Brown Todd LLP’s Commercial Finance practice group and serves as co-chair of the firm’s Multifamily Housing Team. Opinions are the author’s own.

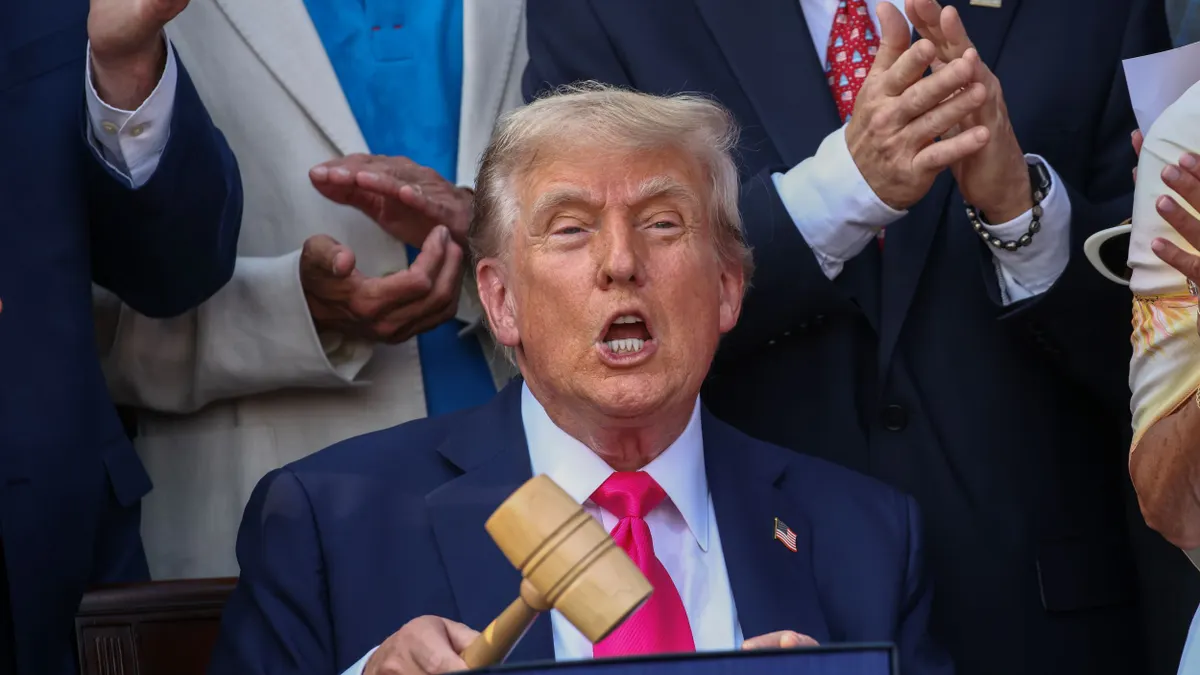

Economic uncertainty over the past few years, whether from inflation concerns or interest rate levels, has led to many developers and investors sitting on the sidelines. Changes enacted by the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, signed into law last month by President Donald Trump, provide a potential way to unlock investor capital and make more deals financially feasible.

OBBBA, among many other things, permanently reinstates 100% bonus depreciation under the Internal Revenue Code for qualified property acquired and placed in service after Jan. 19, 2025.

Section 168(k) of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986 provides a mechanism to depreciate the costs of certain qualified tangible property in the year in which such property is placed in service by the taxpayer rather than over a multi-year recovery period. This accelerated form of depreciation deduction is commonly known as “bonus depreciation” and it is intended to encourage owners to invest in their businesses and properties by providing losses to reduce taxable income.

Over the past few years, the applicable percentage used to calculate the depreciation amount has been phasing out. Specifically, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 would have reduced the applicable percentage to 40% for qualified property placed in service in 2025, 20% for qualified property placed in service in 2026 and 0% for qualified property placed in service in 2027 and thereafter.

Instead, OBBBA permanently reinstated 100% bonus depreciation for certain qualified properties, which could potentially provide significant tax write-offs to investors by accelerating certain deductions that would have previously been recognized over many years.

More demand for LIHTC deals

So, how do developers and investors leverage the newly increased bonus depreciation amounts? Typically, this is done by commissioning a cost segregation study once construction has been completed.

Such a report will identify the portions of the building that could be eligible for bonus depreciation such as certain lighting fixtures, flooring or appliances rather than applying the typical 27.5-year or 39-year recovery periods generally applied to real estate assets. Once the study is complete, the taxpayer’s accountant would apply such findings to increase the amount of losses, which could reduce the taxpayer’s taxable income.

Additionally, this resurrection of 100% bonus depreciation is likely to increase demand for low-income housing tax credit deals and render more deals financially feasible because investors will pay more due to increased tax benefits.

The LIHTC provides a way for owners to generate federal tax credits by creating housing restricted to certain low-income individuals. There are two primary types of credits under the program: 9% credits and 4% credits.

While there are many differences between the programs that developers and investors should know, for purposes of this article the key thing to understand is that a deal using 4% credits uses tax-exempt bond financing while a deal using 9% credits does not.

Prior to OBBBA, to qualify for 4% credits for a building, among other things, more than 50% of the aggregate basis of the land and building needed to be funded with the proceeds of tax-exempt bonds. OBBBA reduced this threshold to 25%, which means that bond issuers could potentially finance twice as many deals as before even though the tax-exempt bond volume cap amounts remained the same.

However, since tax-exempt financing is generally cheaper than taxable financing, developers will need to ensure that they have sufficient equity available to reduce the amount of taxable debt so that the deals will remain viable. As noted above, the increased bonus depreciation amounts could lead to increased pricing (i.e., more equity) from LIHTC investors since 100% bonus depreciation is once again applicable.

OBBBA materially changed the LIHTC program by requiring a smaller portion of 4% credit projects to be financed with tax-exempt bond proceeds, which could make deals more expensive; however, the increased bonus depreciation amounts could lead to better equity pricing to offset such costs.